The Gold Rush

By AG | Monday, 15 September 2003

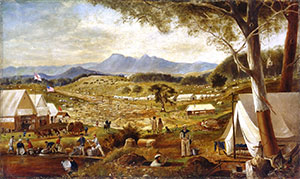

To the populace of crime-torn England at the end of the eighteenth century, a 'free passage' to Australia was anything but a voluntary trip. Yet, in fifty years, Englishmen, and people in countries around the world were prepared to offer their life savings for a berth on a ship to get here. The change in attitude was directly attributable to the discovery of gold around Bathurst (New South Wales) and Ballarat (Victoria).

Gold was first discovered in 1823 (near Bathurst) by James McBrien. The news was kept quiet by the authorities of the time to prevent a convict uprising. By the late 1840's, free settlers had replaced convicts as the main immigrants. By the time the news that a prospector by the name of Edward Hargraves had found gold reached the rest of the world, Australia was already deep in the grips of gold fever. Labourers and settlers alike left their farms, city dwellers abandoned their homes and jobs, and fortune hunters quickly began to flood in from Europe, the United States and the Orient. The opportunity to cash in was quickly grasped by the Government of the day who immediately declared that prospectors and miners must pay a license fee of 30 shillings a month.

Gold was soon discovered at Clunes and then at Ballarat. The frenzied diggers swarmed back, quickly turning Victoria into the golden centre of Australia. The imposition of licenses similar to the ones imposed in the north led to ugly disputes as the miners demanded that the fees be reduced. Tensions quickly reached boiling point in the famous Eureka Stockade clash near Ballarat in 1854.

The Gold Rush opened new roads inland, attracted immigrants and injected much needed cash into the economy. However, when the miners eventually returned home, gold dust and nuggets were not convenient forms of commerce. It was only a matter of time before these raw materials would be struck as gold coin, and in fact the first coins struck in Australia were made from this precious metal.

The first gold coins came into being in a roundabout way following the discovery of gold at Mount Alexander in the Castlemaine district of Victoria. When word hit Adelaide, some 500 kilometers to the west, the rush was on. In the following three months nearly half of South Australia's men were at the diggings. After five months the number stood at 8,000 miners. The drain on manpower had almost peaked to bring on a state of bankruptcy of the colony when about £50,000 worth of gold started to come back in the pockets of the lucky few.

Adelaide Ingots

It soon became apparent that the gold was too difficult to use in it's raw state and on 9th January, 1852, a group of influential merchants approached Lieutenant-Governor Sir Henry Young to start up a mint to convert the gold dust to coin. Sir Henry, at first, refused point-blank, stating that coins could only be struck as part of the Royal prerogative. He was also aware, however, that commonsense would have to prevail. To obtain this consent from the monarch would take at least six months and Adelaide would surely go under in the meantime.

The businessmen appealed again and Sir Henry sought the advice of George Tinline, the acting manager of the South Australian Banking Company. He was in favour of immediate action. They decided on a compromise when the Colonial Treasurer Robert Richard Torrens suggested that ingots and not coins be produced. This had the effect of putting the raw gold into a more convertible form without treading on royal toes.

Sir Henry felt safe. He had found a loophole in the instructions handed down to him by Parliament. While the governors were not allowed to 'assent in Her Majesty's name' to any bill affecting the currency of the colony' there was a way out in the accompanying paragraph which said 'unless urgent necessity exists requiring such to be brought into immediate operation'. This was urgent. So urgent, in fact, that only two hours elapsed between reading the proposed law to the Legislative Council on 28th January, 1852 and having it passed as the Bullion Act Number One. The ingots were not intended as general issue but for banks to hold as backing for their notes. The Act fixed the price of gold at £3-11s an ounce, 9 shillings more than was then being paid in the Victorian goldfields.

They were severely criticised from the word go. It was 4th March when the first ingot appeared and those who saw it were not impressed. They bore no resemblance to the ingots we know today. They were simply a flat strip of gold (some said flattened by a steam roller) which bore an official crown seal and punch figures showing the fineness of the gold which was roughly standardised at 23 and one eighth carats.

The weight of the ingot was also shown, as was a weight conversion to 22-carat gold. Both these figures were punched inside a circular stamp bearing the words 'Weight of Ingot'. They were irregular in shape, some being round and others rectangular, roughly measuring 50 x 25 mm. Many charged that the strips would be easy to counterfeit as the size was not standardised and even the colour of the gold varied - ingots with silver content were pale while gold ore containing copper had an orange tinge.

Thousands of these irregular ingots were produced. Most would not survive for more than a year or two. Today, less than dozen Adelaide ingots are thought to have survived.

The Adelaide Pound (and Five Pounds)

Both the public and the banks wanted legal tender coins, not ingots. Representations were once more made to Sir Henry Young and in November, 1852 the Bullion Act was amended to allow the striking of one, two and five pound issues as well as ten shilling gold pieces. The Adelaide Assay Office had anticipated the move and when the law was adopted, one pound dies already tooled by a local die-maker and engraver, Joshua Payne, were ready to go.

This piece of efficiency was shortlived. After striking no more than 20 or 30 coins, a die-crack was discovered. The crack occurred from the inner circle to the rim beside the downstroke of the 'D' of 'DWT' on the reverse side of the coin. Very few more coins with the Type I design could be struck before the reverse die would completely shatter. A new die was engraved. Although the inscription on the replacement die is similar, close examination of the two types reveals a number of minor differences.

A single, plain-edged lead trial piece, now in the National Gallery of South Australia, is the only undamaged striking known to have survived from the Type I die. All other Type I pieces found so far have the die crack. Should an undamaged specimen be found (now considered possible but unlikely), it would be a great numismatic treasure. About 25,000 of the Type II variety were struck and issued and both coins are now considered to be very rare. Half a dozen five pound coins are believed to have been struck but no records have been found to verify this. None are known to have survived. The design of the five pound coin was similar to that of the one pound and was as large as our 1966 50 cent piece.

In 1919, twelve gold and two silver restrikes of the Adelaide Five Pound coin were especially struck as historical artefacts by the Melbourne Mint, using Joshua Payne's original dies. Six of the gold coins were subsequently melted. Another gold restrike was made ten years later for the National Gallery of South Australia. Should an original five pound coin turn up, it would be regarded as one of the truly rare Australian coins.

Although the Type II was struck in quantity (for that period), few have survived. Soon after striking was completed, it was found that the weight of the gold was worth 1s 11d more than face value. As a result, many were melted down for their intrinsic value, thus ensuring their rarity to collectors who would come generations later.

The semi-official mint of South Australia, known as the Adelaide Assay Office, was to have a short history. Eventually London heard about the makeshift Bullion Act and withdrew Royal assent.