From George II to Elizabeth II - The Story of Currency in Australia

Bank of New South Wales - April, 1954

Acknowledgments

The Bank of New South Wales gratefully acknowledges the assistance in the preparation of this booklet of Mr. O. C. Fleming, President of the Australian Numismatic Society, and of Professor S. J. Butlin, Professor of Economics in the University of Sydney.

Thanks are also due to Messrs. O. C. Fleming, W . G. W right and R. W . Von Bock, members of the Australian Numismatic Society, for permission to photograph coins from their private collections, and to the Trustees of the Mitchell Library, Sydney, for permission to reproduce the photographs of paper currency other than the Bank's own notes.

Definitions

Currency, for the purposes of this story, is taken to include all handto-hand circulating media of exchange, such as coins, bank notes and Treasury notes, and also the promissory notes and tokens of early Australia. All currency is not necessarily legal tender.

Legal tender is the lawful form of payment which a creditor is forced to accept in discharge of a debt. In Australia today, Commonwealth Treasury notes are legal tender to an unlimited amount, silver coin up to forty shillings and bronze up to one shilling. A creditor may, of course, accept payment in other forms if he wishes.

In early Australia, with practically no forms of legal tender available, currency was more often not legal tender than otherwise.

Introduction

This booklet is intended to show how some of the interesting facets of Australian history are reflected in the currency of the country at various stages of its economic growth.

Both the currencies of earlier years, and those of today are of considerable interest from the standpoint of history. History is reflected in the world's currencies, not completely, but sometimes very pertinently. And while the average history student may not find in coins or notes the same pleasure that the ardent numismatist achieves, he may be surprised by the way they landmark some of the more significant developments. So, though we, in Australia, have comparatively few coins of Australian origin, yet those we have, and the other currency used in Australia since the first settlement, are part of the tapestry of our short but energetic history.

Coins have been used as a medium of exchange for almost 3,000 years. They have taken many forms, from the gold coins of ancient Greece to the knife money of China ; from the lumpy tical of Siam to the Dresden porcelain coins of Germany. But whatever their shape or substance, they have always represented value.

They replaced the system of barter, in which one product is exchanged for another (much in the same way as at school we might swap marbles for stamps or autographs) quite logically ; for until comparatively recent years coin normally had an intrinsic value approximate to its value as money. Thus in the early days, gold always having been a much prized metal, a lump of gold of a certain weight might be reckoned fair value for a sheep or an ox, or a quantity of grain. Coins of gold, being of constant weight, simplified payments. Silver, considered less valuable than gold, could, in suitable coined sizes, be reckoned as fractions of the value of a gold coin ; and later, copper, also on its market or demand value, as fractions of silver coins.

From these beginnings our present coinage grew, although today the intrinsic value of coin is not intended to equal its purchasing value, but rather it is a token currency guaranteed at a certain value by the government which issues it. Paper money of course, is also a token currency ; more convenient than coin where larger amounts are involved.

Forms of Currency from 1788 to 1817

When arrangements were made for the establishment of a penal settlement in the Colony of New South Wales, no provision was made for an internal currency. Convicts received no wages, and the needs of the civil and military personnel were to be supplied from the Commissariat or communal store. The Colony was intended to be selfsupporting, its own produce being used to replenish the store. This, however, did not come about for many years, as not only were farming conditions in Australia far different from those of England, but the previous occupations of most of its inhabitants, the convicts, were not generally the most suitable for agricultural and pastoral success.

Yet with the gradual increase in the numbers of free settlers and emancipists, and much individual enterprise, the land began to yield some reward. And with it increased the commerce of the Colony. The need for some form of currency could not now be denied.

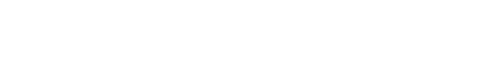

A quantity of Spanish dollars, at the time an almost international currency with a silver content of the value of about five shillings, was sent from England in 1792. Some other coin was undoubtedly brought out in both the administrative and penal pockets of the first fleet and subsequent transports. If all this had remained in Australia, it would have helped to some extent to alleviate the scarcity of coin. But the opportunities for trade, for buying goods which the Colony could not produce, presented by the visits of merchant ships, resulted in coin, the only item of value in the Colony for ready exchange, leaving almost as fast as it arrived.

By 1800, the following methods of payment were used in the Colony. The Store Receipt, issued by the Commissariat in exchange for its purchases within the Colony.

- Bills on the British Treasury, used for payment for goods purchased by the Government from overseas.

- Barter- the exchange of commodities for labour or other produce.

- English shillings and copper pennies. (The latter, weighing one ounce each, were know n as cartwheels and were given a local value of twopence. They were the first regal copper pennies.).

- Spanish dollars in small quantities.

- Private promissory notes.

- A few British and Irish bank notes.

- A number of foreign coins from many parts of the world, including Portuguese johannas, Indian rupees, Ceylon pagodas, Dutch guelders, gold mohurs and ducats.

With such limited supplies of coin available for internal use, and barter having such obvious limitations as a form of trade (produce available as barter not always being acceptable to a second party), private promissory notes, or I.O .U .'s, came into general circulation. Indeed, before long they largely took the place of coin.

Promissory notes, however, had many disadvantages, at least to the honest citizen. They were issued by all and sundry, from the Governors of the Colony to the meanest convict. They were forged, issued in fictitious names, and issued without collateral (i.e. the issuer having no possessions which might be sold or offered in return when the notes were to be redeemed), so their acceptance was certainly not without risk. Thus storekeepers might accept promissory notes at a discount, or under their face value, in the hope that they might so offset possible loss.

There were unscrupulous men in the settlement who took advantage of this practice of discount. Governor Macquarie, in a dispatch to England, cited a case where a man issued promissory notes to a considerable amount for the purchase of goods and then had a rumour put about that his financial position was unsound. Even in the big cities of today rumours travel with amazing speed ; in a small town such as the Sydney of Macquarie's day they would soon be known by all, with a resultant rush to get rid of these notes at whatever price could be obtained. In the circumstances there would not be many buyers and the issuer's agents would buy back the notes at as much as 75 % below their face value, thus securing for him a handsome profit on his original purchases.

Various attempts had been made by Governors King, H unter, and Bligh to bring promissory notes under control, but without success. Their indiscriminate issue and their acceptance continued, in spite of government regulations, for there was no other currency to replace them. All early attempts to keep coin in the Colony met with similar failure and it was impossible to get anything like adequate supplies of coin from England, herself in the throes of a severe shortage of coin. This was due to various factors including extensive use of gold to finance the Napoleonic wars, the exhaustion of the silver mines in England, a general rise in the price of silver, and a temporary public distrust of paper money. Coupled with these was the fact that most of the coin that was in circulation in England was badly worn or mutilated (dishonest people making a practice of clipping or shaving the rims of coins, to collect precious metal). The value of the coins was thus often less than their face value and the coinage could not have been recalled and new coins of correct weight issued in its place except at great expense. It is not surprising therefore that with the coin situation in the M other Country so chaotic, the new Colony of New South Wales, on the other side of the world, had little chance of obtaining even a moderate supply.

It was not until 1816-17 that a great re-coinage eased the shortage of coin in England and, eventually, in Australia.

Apart from promissory notes, the only other readily available form of exchange was barter. A labourer could be paid for his toil with tea, flour, sugar, rum (the local term for all spirits), or any other item in demand. Bakeries might sell bread for cash or for so much flour. The Commissariat would accept certain items of which it was at the time in need, such as cattle or grain, in return for its supplies. Governors were not averse to paying in kind and Governor Macquarie purchased houses, built roads, and made other governmental purchases paying for them in quantities of spirits. The old Sydney Hospital, still standing today, was built in return for a monopoly in the import of spirits for three and a half years. As most things, including spirits, sold at inflated prices in the Colony, this should have proved a very profitable deal for the builders.

The first successful attempt to prevent the export of coin was with the holey dollar. It was Governor Macquarie's firm intention that the 40,000 Spanish dollars which the British Government sent to the Colony in 1812 would not, like previous imports of coin, find its way into trading ships and thus be lost to the Colony as a circulating medium of exchange. He therefore had the centre of each dollar punched out, leaving a ring and a dump.

The ring dollar, later called the holey dollar, was overstruck with the inscription New South Wales 1813 on one side and five shillings on the other. The faces of the dumps were cleaned to leave a smooth surface, and were struck with the inscription New South Wales 1813 with a crown in the centre on the obverse, and Fifteen Pence on the reverse. This practice of m utilating coinage was not original for ring dollars had been used previously in other colonies.

The holey dollar and dump together now had a value of 6s. 3d. against the dollar's original value of approximately 4s. 9d., which was profitable to the Government, and they were easily identifiable in the event of any attempt being made to export them from the Colony. The increased value alone would not have prevented their export, as shipmasters would simply have increased the prices of their goods to offset the greater value given to the coins, as had been done when previous Governors had inflated the local value of coinage. Their retention in the Colony was due rather to the very severe penalties with which Macquarie threatened anyone found engaged in their export.

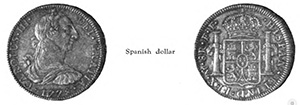

Macquarie also gave considerable attention to the matter of promissory notes. W hen he arrived in the Colony he was anxious to see the establishment of a bank, which, he felt, would, in issuing bank notes, resolve this problem. His plan was not acceptable in London and he was forced to abandon the idea temporarily. In 1816, however, at his instigation and with his support, a public meeting was called and subscribers came forward to finance Australia's first bank, the Bank of New South Wales. O n 8th April, 1817, the Bank opened for business and, although it passed through some anxious moments in its early years, it has grown to become ' Australia's largest bank, with branches throughout Australia and New Zealand and in Fiji, Papua and New Guinea, and London. The Bank issued notes for 2s. 6d., 5s., 10s., £1 and £5, the latter two denominations being the most important.

Dollar and Sterling Currencies

The establishment of a bank did not, however, provide the answer to the shortage of currency, its note issue being small in comparison with that of the Commissariat. By 1822, in fact, owing to further large imports of Spanish dollars, the dollar had become the basic currency of the Colony. This was also true of the settlement at Van Dieman's Land. There was agitation to make the dollar the official currency of the Colony and legislation passed earlier by Macquarie prohibiting the use of dollars except holey dollars was repealed. Holey dollars and dumps were recalled and reissued as threequarter and quarter dollars respectively. It was also intended to give the halfpenny the value of one cent, or one hundredth of a dollar.

In 1825, however, the British Government passed legislation to provide for a basic English sterling currency to be used in the Colony and in 1826, the Bank of New South Wales, which had been issuing its notes in terms of Spanish dollars since 1822, returned to issuing in terms of sterling. Dollars still continued to circulate but by the 1830's few remained in New South Wales, although it was not until 1842 that they ceased to be legal tender in Tasmania.

Until 1909, British coin was then the only official currency, with the exception of the Sydney Mint issues of 1855 to 1870, and circulated freely until 1931, when the Australian pound, previously w orth a pound sterling, was devalued.

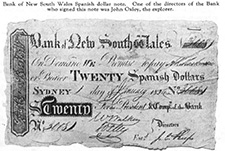

Private Tokens

We have seen that the solving of the problem of the chronic shortage of coin periodically concerned Governors in the early days. The private token was an attempt by private individuals to combat the same inconvenience.

Except for one isolated instance of the issue of a silver token in Tasmania dated 1823, the first tokens made their appearance in Australia Bank of N ew South Wales Spanish dollar note. One of the directors of the Bank who signed this note was John Oxley, the explorer. in 1849. They were issued by men of commerce as change and were generally made of copper, about the same sizes as a penny or halfpenny being used in place of those coins. They normally bore the name of the issuer on one side and a design of some sort on the other. However, whilst British coin was guaranteed by the Government, tokens had only the guarantee of the issuer, with little chance of redress should he become insolvent. The value of the pure copper used in the manufacture of most tokens, however, approximated the purchasing value given to them.

Tokens at first gave relief to the shortage of small change, but later, with the import of the new bronze coinage of England of 1860, became a nuisance and were declared illegal. Tasmania was the last to pass legislation for this purpose, in 1876.

Gold

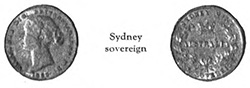

The gold discoveries in Victoria in 1851 gave rise to the issue of the first coin that can be described properly as Australian, the Sydney sovereign.

The Royal Mint, London, is responsible for the issue of all British coin and thus the British coinage in use in Australia from its inception had either been minted at the Royal Mint or by a private contractor under its authority. W ith large quantities of gold being mined in Australia, it became desirable to turn some of this into coin in the colonies themselves. Thus branches of the Royal Mint were established in Sydney in 1855, in Melbourne in 1872, and in Perth, following the West Australian gold rush, in 1899.

Until after Federation these minted gold coin only. The issues of sovereigns from the Sydney Mint from 1855 until the close of 1870 were distinctive in design from the British sovereign, bearing the words Sydney Mint Australia on the reverse. These were intended to be legal tender in the Colony of New South Wales only, recently reduced in area by the formation of the Port Phillip district as the separate Colony of Victoria, but legislation was later passed in Victoria to make them legal tender in that Colony as from 1857. As they actually contained a little more than a sovereign's worth of gold it could not have made much difference to their acceptance throughout the world.

All subsequent issues of gold coin from Australian Mints were identical with the British sovereign except for a distinguishing mark or mint mark to identify their place of manufacture. The marks used by the Sydney, Melbourne, and Perth Mints for this purpose were S., M., and P. respectively. Of all the official issues of gold coin in Australia, only the early issues of the Sydney Mint mentioned above can be really described as Australian.

Only one other gold coin was struck in Australia. This was a one pound piece issued for a brief period by the Assay Office of South Australia. The shortage of coin in South Australia, together with the quantities of gold dust then available, was the reason for these coins. They were struck under the authority of the South Australian Governor, with the support of the local parliament. The Assay Office also accepted gold dust for melting into ingots of suitable sizes, with the weight of each ingot stamped thereon. These were intended for melting down again at some future date and it is thus not surprising that few specimens exist today. Australia finally went off the gold standard, where its currency was convertible into a certain weight and fineness of gold, in 1932, and gold coin ceased to circulate.

A Separate Australian Currency

There was some agitation for the issue of an Australian coinage in the 1890's and permission was granted by the British Government. Federation, however, was the important issue of those days and the matter of an Australian coinage was deferred until after that had been achieved.

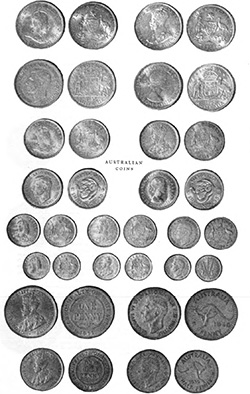

It was not, in fact, until 1910, that the first coins of the Commonwealth were issued. These, silver issues only, were m inted by the Royal Mint. In the same year a prohibitive tax was imposed on the issue of bank notes. These were not legal tender but had been issued by banks ever since the first bank in 1817 and were redeemable in gold coin. The States were also now prohibited from issuing their own notes, as had been done by the Queensland Treasury. These were replaced by Commonwealth Treasury notes which were legal tender in all States. Until 1932 the Commonwealth notes bore the promise of the Treasurer to redeem in gold coin, but now carry the inscription that they are legal tender in the Commonwealth and in all Territories under the Control of the Commonwealth. The area of legal tender for Australian coin is, of course, the same.

From 1911 to 1915, Commonwealth coin of both silver and copper were struck at the Royal Mint, London, or at Birmingham, by Heaton and Sons, contractors to the Royal Mint. In 1916, the Melbourne Mint was ready to take over the minting of silver issues and the copper issues were struck at the Calcutta branch of the Royal Mint. From 1919 until during the 1939/45 war (when in some years the Australian mints were unable to m int the number of coins required and additional coins were struck in the United States and India) all silver and copper coinage was minted at either Sydney (closed in 1926), Melbourne, or Perth. Since the war, the only issues to be minted outside Australia were sixpences, threepences, pennies, and halfpennies of 1951 minted at London. A m int mark appears on these issues, and they are the first coins used in Australia, either of British or Australian design, on which the Royal Mint London has placed a mint mark. The mint mark is P.L. and is of particular interest in itself.

Debasement of Australian Silver

Due to the high price of silver after the 1914/18 war, the silver coinage of England had given place to coins containing only 50 % silver and 50 % alloy, i.e., token coins. The English silver was thus debased or of less intrinsic value than before.

Australia considered following suit, but before any action was taken the price of silver fell and the necessity disappeared. The 1921 shilling, with a star above the date, was designed to be the first of the proposed alloyed Australian coinage. It was, however, issued in silver as before. Nickel pence and half pence were also contemplated for replacing the heavier and larger bronze pieces and sample pieces or patterns were made. These were considered for some years but were finally rejected. Australia did not again consider debasing its silver coins until 1947 when the price of silver rose again and caused the production of a silver coinage of 50% silver and 50% copper nickel alloy which is still used in our current issues.

Mint Marks on Coins of the Australian Commonwealth

As we now know, all the coins of the Australian Commonwealth have not been minted in Australia, and those that have may have been minted at any one of three Australian Mints. Even today, we have had coins minted in London as recently as 1951, and there are two Australian mints still in operation. As a matter of interest, the following information has been included which should make identification of the mints responsible for striking most of our currency quite easy.

| No mint mark | Before 1916 | Royal Mint, London |

| No mint mark | Silver from 1922 and copper from 1920 | Melbourne Mint |

| D | Denver, U.S.A. | |

| H | Heaton & Sons, Birmingham, Contractors to the Royal Mint | |

| I | Calcutta Mint, India | |

| M | Melbourne Mint | |

| P.L. | Royal Mint, London | |

| On George V penny | Dot above the lower scroll on reverse side | Sydney Mint |

| On George V penny | Dot below the lower scroll on reverse side | Melbourne Mint |

| On George VI penny and halfpenny | Dot after the word penny on the reverse side and dot after the word Australian from 1952 | Perth |

These mint marks are not hard to find on coins in good condition, the initials of the designers of the coin faces, however, also appear on most of our coins and may prove confusing without the following explanation.

| Initials | Name of designer | Details |

|---|---|---|

| DeS. | George William de Saulles | Appears on the obverse of Edward VII issues |

| B.M. | Bertram MacKennal | Appears on the obverse of George V issues |

| H.P. | Herbert Paget | Appears on the obverse of George VI issues |

| K.G. | George Kruger Gray | Appears on the obverse of George V commemorative issues, and on George VI and Elizabeth II issues |

| M.G. | Mary Gillick | Appears on the obverse of Elizabeth II issues (The initials M.G. are extremely difficult to see except on new coins of the 1953 issues and are placed on the base of the Queen's Image) |

| W.L.B. | William Leslie Bowles | Appears on the reverse face of the Elizabeth II 1954 Royal Visit Florin (Mr. Bowles also designed the reverse face of the 1951 Jubilee Florin but his initials were not included in the design) |

The reverse designs of the Edward VII and on George V issues (other than the two commemorative issues) are Royal Mint designs which carry no designer's initials.

Australian numismatists and others who examine their 1951 coins with more than the customary glance will have already observed that some of them (in fact, those struck in the United Kingdom) bear on the reverse a diminutive PL. This is a mintm ark. The same letters were used, as well as others, for the same purpose on coins struck at London during the Roman Occupation. No contemporary expanded version has yet been found and 1 will not venture to judge between the various suggestions as to the full form. Prima (officlna) Londinnil, Londiniensis or Londinio- the first workshop of London, the first London workshop or the first workshop at London- all have well-qualified champions. Some suggest that P is an abbreviation of pecunia; others favour percussa. Whatever be the extended form, how ever, the significance was the same in 1951 as in Roman times, that the coins were struck In the Mint in London. Extract from Eighty-Second Annual Report of the Deputy Master and Comptroller of the Royal Mint 1951.

Commemorative Issues

Canberra Florin

The Canberra Florin was the first commemorative coin struck in Australia. It was issued in 1927, the year the then Duke of York, later King George VI, opened Parliament House Canberra, which is depicted on the reverse side of the coin.

Victorian Centenary Florin

Bearing the date 1934/35, this coin was struck to commemorate the centenary of the first permanent settlement in Victoria, then the Port Phillip District of the Colony of New South Wales. This was the second commemorative issue and the first and only coin ever issued at a premium on its face value. It was sold at three shillings, the extra shilling helping to finance the cost of the centenary celebrations.

The Australian Crown

The Australian Crown is the only coin issued bearing the date 1937. It was struck to commemorate the coronation of King George VI. It was issued again in 1938 and for that reason is not now regarded by numismatists as a purely commemorative issue.

1951 Jubilee Florin

The Jubilee Florin was issued to commemorate the first fifty years since the Federation of Australia.

1954 Royal Visit Florin

Issued in January 1954, this florin commemorates the Royal visit to Australia of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and His Royal Highness, the Duke of Edinburgh.

Conclusion

As we have seen, the currencies of both past and present years have a tale to tell, if only we search a little into their history. The Johannas, the Guilders, the Pagodas and their companions circulated in Australia because no provision had been made for a currency for the Colony of New South Wales. The dollars, which circulated for the same reason, were mutilated and became ring dollars and dumps so that they could be easily identified should an attempt be made to take them from the Colony. The fact that early Australia was not nor could for many years be selfsupporting was a main cause for the export of such coin as did arrive from England. The shortage of coin in England was the reason for only inadequate supplies of English coin being made available to the Colony until the 1820's with the consequent temporary dollar currency. Gold discoveries in Australia were the reasons for the establishment of branches of the Royal Mint at Sydney, Melbourne, and Perth. Tokens came into circulation because of a temporary shortage of small change and the South Australian pound piece was struck to provide coin for South Australia. The issue of an Australian coinage was delayed by more important considerations of Federation. Bank Notes and Queensland Treasury Notes went out of circulation with the advent of the Commonwealth Treasury Notes of 1910. Gold coins were withdrawn from circulation when Australia went off the gold standard and the intrinsic value of our silver currency was reduced because of the increased market value of silver. And special commemorative issues mark some of the nationally important occasions of recent times.

So in the currency used in Australia since 1788 we can trace some of the developments of Australian history, and those outlined herein by no means constitute the full extent which study can reveal. In studying the development of this still expanding and prosperous country, we should be able to look more confidently to the future, careful to avoid any doubtful practices of the past, but ready to take example from the honest courage and initiative on which the real success of Australia has been built.