The New Zealand Waitangi Crown of 1935

By Mark Stocker | Friday, 1 January 2010

Introduction

The crown piece of 1935, popularly known as the Waitangi Crown because of its reverse design and exergue inscription, occupies a special place in the numismatic history of New Zealand. As a work of art, it is surely less startling than the British Silver Jubilee crown of the same year by the same designer, Percy Metcalfe, which depicts a bareheaded St George on a clockwork horse vanquishing a very angular wounded dragon.

1935 New Zealand Waitangi Crown

But whereas almost three-quarters of a million of the latter coins were produced, there were just 1,128 Waitangi Crown pieces. Already classified by Allan Sutherland in his Numismatic History of New Zealand (1941) as very scarce, it is the rarest New Zealand non-gold coin apart from the so-called 1879 Pattern Penny by Allen & Moore of Birmingham, which is properly accorded token status.

Why were so few crowns produced, even for a Dominion whose population barely exceeded one and a half million at the time? Although the surviving documentation fails to answer this question explicitly, several possible explanations are offered at the end of this article.

While the coin's rarity and attendant monetary value have understandably preoccupied collectors, further factors underlie its numismatic and aesthetic interest. The crown raises still highly relevant cultural questions of Maori and Pakeha (New Zealand European) identity and how New Zealand in the 1930s viewed and reconstructed its past. In examining the circum stances behind the crown's design and production, this article will also explore the relationship between a dominant New Zealand Minister of Finance, Gordon Coates, and his equally imperious counterpart at the Royal Mint, the Deputy Master, Sir Robert Johnson. Art historical questions of what was later called Art Deco design and its critics will be raised.

Another important consideration is the role and response of the recently founded (1931) New Zealand Numismatic Society in relation to the coin. Its documentation is relatively better than that for the 1939-40 halfpenny, penny and commemorative half-crown. This is partly thanks to the extensive and still uncatalogued papers deposited at the Auckland Central Library of that dominant figure in mid-twentieth century New Zealand numismatics, Allan Sutherland (1900-1967).

Further invaluable documentation of the coin's lengthy design process survives in Royal Mint files at the National Archives, Kew, in the form of correspondence, memoranda and, importantly, illustrations of trial designs. Less copious but still useful are early transactions of the New Zealand Numismatic Society.

Why was the crown issued?

One of the earliest recorded references to a crown piece is in the draft typescript of a letter dated 17 October 1933 from Sutherland to the Secretary of the Treasury, A.D. Park. Sutherland was directed by the Council of the New Zealand Numismatic Society, as its honorary secretary, to submit a proposal for a limited issue of crowns in specimen or collectors sets, on the lines of the Imperial practice'. Although crowns were common currency neither in Britain nor in New Zealand, Sutherland stated that every time there is a change in the design of Imperial coins, a new crown is issued to keep the denomination alive, and incidentally, the profit to the State is considerable. Such language was calculated to appeal to a senior Treasury official and befitted the man who later became editor-in-chief of New Zealand Parliamentary Debates (1957-62). Sutherland recommended no fewer than 10,000 collectors sets to be sold from the Royal Mint', claiming that the demand for specimens of an entirely new coinage, such as the New Zealand issue, should be equally as great, if not greater – if the designs are attractive. Sutherland was well placed to make this submission through his membership of the governmentappointed coinage design committee convened by Coates. It had recently been working with the Royal Mint on New Zealand's first national coinage, which featured new reverse designs from the half-crown to the threepence, by George Kruger Gray. These were on the verge of completion and circulation at the time.

In a personal letter to Park, Sutherland reiterated the point and drafted a helpful public announcement stating that Single specimens of the first issue of the crown will not be available other than in collectors sets, the issue of which will be strictly limited'. Future crowns, he believed, would be sought after, not only by collectors wanting specimen sets but also by non-collectors aspiring to possess an unusual or large coin.

Commemorating Waitangi

Sutherland – and the Society – proved persuasive. Before the matter became public knowledge, at a meeting on 15 January 1934, members expressed gratification at the decision of the Government to issue crown pieces for numismatists, in keeping with the Imperial practice. The crown reverse would bear a Waitangi design, to honour the name, location and political significance of New Zealand's formative constitutional document, the Treaty of Waitangi, signed between Maori and Pakeha representatives in 1840.

Privately, Sutherland expressed reservations about the suitability of the subject matter, sentiments that were shared by Professor John (later Sir John) Rankine Brown, President of the Society and a fellow design committee member. This was because 1940, the centenary of the Treaty, seemed to them a more appropriate date of issue for such a coin. Furthermore, at the time, the Society itself was planning to commission a limited edition medal to be struck in honour of the GovernorGeneral, Charles Bathurst, Viscount Bledisoe and the nationalisation of Waitangi.

The mana (spiritual power and prestige) of this medal would inevitably be somewhat compromised by a large, high value coin on sale to the general public. But any such numismatic sensibilities were swept aside by Coates, who was hardly disposed to wait another six years for the centenary. Brown was left to complain impotently of how politics... entered the question.

James Berry, Bledisloe Medal for the New Zealand Numismatic Society, 1934 (presented 1935) (diameter 51 mm).

Waitangi dominated the news at the time and marked a welcome diversion from the economic depression. Bledisloe had organised and personally contributed towards the purchase of the Mangungu Mission House, where the Treaty was signed, together with surrounding land. The site was formally dedicated to the people of New Zealand at the anniversary celebrations of 5-6 February 1934. Before a crowd of some six thousand Maori and four thousand Pakeha, a newly erected thirty metre flagstaff, two visiting naval ships and a guard of honour of 150, Bledisloe laid the foundations for a new whare runanga (meeting house) on which was inscribed Ko te papepae tapu o te tiriti o Waitangi (the sacred threshold of the treaty of Waitangi). The event has been widely regarded as marking the modern history of Waitangi and of the Treaty. Coates capitalised on the occasion by going public on the proposed coin. Under the headline Waitangi Emblem: New Five-Shilling Piece, the Auckland Star reported the Finance Minister's announcement at the conference with the Maoris today that the five-shilling piece of the new Dominion coinage will be a representation of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi:

The Minister said the decision had been made early that morning [sic]... the representation of the treaty scene would include the figures of the first Governor of New Zealand, Captain William Hobson, R.N., the Rev. Henry Williams, one or two other missionaries, Tamati Waka Nene and other chiefs. The pictorial representation would convey the message that the treaty meant everything to the people of New Zealand. Like the half crown and sixpence which have recently been put into circulation, the new five shilling piece was designed by Mr George Kruger Gray.

Rejected designs by James Berry and Kruger Gray

This last statement was both premature and inaccurate. The person entrusted with providing the initial designs was in fact James Berry (1906-1979), a Wellington-based commercial artist who was then at the outset of his career as one of New Zealand's most successful and prolific designers of coins, medals and stamps. The circumstances of his commission are unclear, but it seems likely that Berry was approached either by the design committee or by Sutherland himself. He was also commissioned to design the Numismatic Society's Bledisloe and Waitangi medal, mentioned above. In his correspondence with Sutherland, Berry adopted a polite, almost deferential tone, and asked him whether twelve or fifteen guineas was a suitable fee to request from the Treasury for his work. Berry's drawings were primarily intended, as Sutherland stated, to serve as guidelines for the coinage artist attached to the Royal Mint in the preparation for the design. Sutherland later explained to Johnson how the design was taken from the bas relief of a Wellington statue showing Maori chiefs signing the Treaty.

James Berry, design for crown, 1933.

This referred to one of Alfred Drury's bronze reliefs on the pedestal of his Queen Victoria Memorial in Wellington (1902–5), whose design would in turn be reproduced on the 1940 Reserve Bank of New Zealand ten shilling banknote. Sutherland believed that there is no overcrowding as one might expect in the composition. A surviving drawing that correlates with this description is reproduced in J.R. Tye's monograph, The Image Maker: The Art of James Berry (1984), but this suggests a conclusion different from Sutherland's.

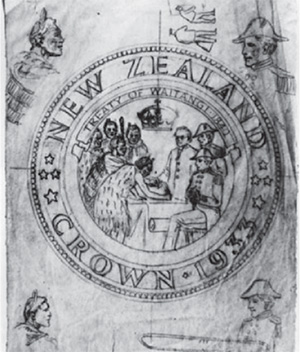

The Royal Mint Standing Committee on Coins, Medals and Decorations met in June 1934, when it considered two pairs of designs for the crown. Their authorship was not identified but all of them were probably by Berry. The sole surviving design in the Royal Mint album at the National Archives is a photograph of a plaster relief, which bears the initials of both Berry and Kruger Gray. Clearly the latter had modelled one of Berry's designs and from archival evidence, this had been executed relatively rapidly. The relief corresponds to Berry's description of an alternative design to the group of chiefs, which will depict the two main figures Captain Hobson & Waka Nene & something symbolic of Waitangi in the background.

In the event, the only background feature is the inscription WITANGI 1840. Maori spelling was not Kruger Gray's forte, as he ruefully recognised when it was too late. Kruger Gray had little faith in either the group design – the signing of the Treaty he thought impossible for a metal coin – or indeed in his model of the alternative with two figures: I'm afraid it is pretty bad. He claimed that Hobson's uniform, as depicted in the Drawing which the New Zealand people have made, was quite incorrect and he had thus altered it to the best of his knowledge, using a print dating from 1848. He had, however, followed the design in the main, including, for instance, a decorative frame based on traditional Maori rafter patterns (kowhaiwhai).

Model for crown, 1934 (photograph of plaster relief).

In the event, neither pair appealed to the Committee, which was unanimously of the opinion that the designs as submitted by the Dominion were quite unsuitable for a coin or even a small medal. They were considered too pictorial in character and, moreover, included far too much detail for successful representation in metal or coin size. Mr. Kruger Gray's modelled design received no commendation. When pressed by Johnson to indicate a preference, the Committee conceded that the design with two figures offered greater possibilities. Sir William Goscombe John, a distinguished survivor of the New Sculpture movement, suggested that Mr. Metcalfe should be invited to try his hand. Although A.D. (Athol) Mackay, the Finance Officer at the New Zealand High Commission and a major figure in subsequent negotiations over the coin, rightly believed that the authorities back home would not welcome the abandonment of the ideas submitted, nor of any considerable departure from the designs, after lengthy discussions the Committee suggested that alternative designs commemorating the Waitangi treaty by approved medallists in this country [Great Britain] could, if desired, be submitted. We hear no more from the disaffected Kruger Gray, but within six weeks Percy Metcalfe's first designs for the crown were being considered by the Committee.

Percy Metcalfe's first design

Their visual origins deserve speculation. Berry had earlier told Sutherland that he had also drawn an alternative centre piece with the two figures keeping the crown between the heads. Perhaps Metcalfe received such a drawing, as his designs correspond to this description. However, there is little or no visual evidence to suggest any further involvement by Berry in the design. At the June meeting, Goscombe John had suggested that something might be made of the figures if they were treated ... say, after the manner of Flaxman. He was probably thinking of John Flaxman's famous Wedgwood jasper relief, Mercury Uniting the Hands of Britain and France (1787), where personifications of the two nations, rendered in strict profile, shake hands to commemorate the Anglo-French Commercial Treaty of 1786. Metcalfe modified Flaxman's graceful Neo-classical aesthetic into a contemporary Art Deco idiom, which is at once more hard-edged and virile. The static, profiled figures are strongly evocative of the Egyptian Revival, which was a significant Art Deco sub-style.

Metcalfe's work in turn has close affinities with that of the sculptor Charles Sargeant Jagger, who had earlier employed him as a studio assistant and was a fellow Yorkshireman and Royal College of Art graduate to boot. Prior to Jagger's untimely death in November 1934, he was Metcalfe's staunch advocate on the Advisory Committee.

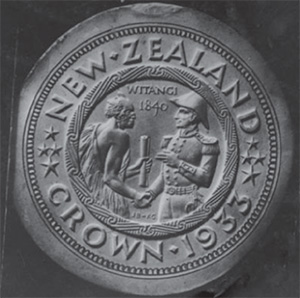

Percy Metcalfe, fi rst design for crown reverse, July 1934.

At the next Advisory Committee meeting in late July, Metcalfe's first design, in the form of photographs of a 3-inch diameter model, was generally approved of and considered a distinguished work. Minor improvements were, however, suggested. Hobson's right trouser leg should not be quite so tubular in form, and if possible, the boot should not be concealed behind the foot of the Maori chieftain. Strap trousers were probably worn at the date in question. Hobson's chest was considered a little too bombé and might be improved, while the accuracy of his military stripes needed verification.

Questions over the date were also raised; 1933 was initially used to be consistent with the other new coins, but this appeared odd in view of the fact that the crown could not hope to be struck before late 1934. Neither the Advisory Committee nor Metcalfe himself appear to have been properly briefed about the particular significance of the events at Waitangi in the previous February. In terms of historical accuracy, it was asked Should Capt. Hobson be shown wearing a beard and whiskers? Advice was also sought on the accuracy of Nene's features.

While Mackay believed that his hair was not quite correct, there is no recorded mention of the absence of moko (facial tattooing). The latter would, however, feature in all of Metcalfe's subsequent designs. Mackay expressed reservations about the rendering of Nene's ceremonial cloak, which he believed should be definitely of small feathers. This was not necessarily correct. In his pioneering history of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, William Colenso claimed that a variety of cloaks were worn for the occasion, including splendid looking new woollen ones, probably of French manufacture, while other Maori wore customary and in some cases European dress. According to Patricia Wallace, it is likely that Nene wore a kahu kuri or dog skin cloak. He surely wore nothing quite like Metcalfe's creation, which looks as if it were composed of neat rows of plantains. Metcalfe's hard-edged style, while unquestionably powerful, was less suitable in this context than the more delicately pictorial approach of Kruger Gray. Understandably, neither artist could claim cultural familiarity with the subject matter involved, and both of them had earlier encountered difficulties in the naturalistic rendition of the kiwi for a lower denomination reverse.

The interventions of Gordon Coates

Photographs of the designs reached Wellington in early September 1934. Coates responded discouragingly by requesting temporary suspension of work, pending further instructions. He eventually sent these to Mackay in a telegram of mid-November. Coates found Metcalfe's designs disappointing, especially as regards features, neither faces [sic] bear any resemblance to personalities intended to be depicted. He itemised the following faults: Firstly: Wrong leg forward. Secondly: Both legs too rigid as Maori not seen with legs quite straight but always on the alert. Thirdly: Right leg and left forearm of Maori too unshapely, and right arm unduly long. Unless the cloak could be correctly reproduced, Coates suggested its replacement with a flaxen piupiu kilt, with the implication that Nene's torso be left naked, like that of a common Maori warrior. In retrospect, the very notion of the topless Nga Puhi tribe rangatira (chieftain) signing the treaty appears a graver solecism than Metcalfe's cloaked figure, for all its inaccuracies. Coates also instructed that Metcalfe be provided with photographs taken of Maori at the recent celebrations that featured in the Auckland Weekly News. These would assist him with regard to following points smooth modelling and proportion(s) powerful limbs also typical posture of figures, also correct position of cloak [sic]. Lastly, and perhaps most persuasively, Coates recommended a smaller crown motif.

In a letter to Mackay, Sutherland echoed Coates's sentiments:

...negotiations have been proceeding with alternative [designs]. It was ever thus. We do not mind the delay so long as we get a good design. The last design submitted was prepared by Metcalfe who was unsuccessful with our other designs... The only difficulty about the latest design is that Metcalfe is an impressionist and his style is not in keeping with Kruger Gray's more natural style shown in the coins already issued. The series should be uniform in treatment. This means a little further delay.

While the impressionist label would have probably baffled Claude Monet, Sutherland's wary conservatism towards what we would today call the Art Deco aesthetic is manifest. He had earlier criticised Metcalfe's unadopted designs for the reverses of the lower denominations on similar grounds, although he evinced respect for the artist in his correspondence with Johnson. In later years Sunderland's stylistic conservatism proved decisive in the adoption of New Zealand's first decimal coins (1967), where James Berry's designs for the reverses were favoured over the more sophisticated modernism of Paul Beadle, Milner Gray and Eileen Mayo.

Metcalfe's modifications

Metcalfe, design for crown, July–September 1934.

Meanwhile, unaware of Coates's moratorium, Metcalfe had been revising the model in the light of the July meeting of the Advisory Committee. Several of the objections coming from the New Zealand authorities no longer applied. In his new design, he replaced Nene's cloak with a piupiu and reversed the position of his legs, as well as introducing creases on Hobson's trousers to render them less tubular. Hearing the latest requirements from Coates, Metcalfe told Johnson: ... if it were strongly felt that the crown should be smaller, I would alter it, but from a design point of view, not willingly. He was obviously frustrated by his reliance on the response of Coates and the New Zealand committee, with the delays and setbacks that this entailed. Encouragement on the spot from Mackay carried limited clout in New Zealand. Metcalfe thus felt in need of someone who will decide what final amendments should be made and suggested that the High Commissioner would be suitable for such a role. Had Metcalfe known it, Sir Thomas Wilford, then nearing the end of his term, would have proved no match for Coates.

Coates made his position clear in a telegram of 28 November, which bluntly stated: I am not prepared to accept present arrangement limbs and size of hands being quite unnatural and not typical Maori. Johnson's response – directed at the patient Mackay – was caustic: I have no idea... in what way the limbs and size of Maori hands differ from those of ordinary human beings. A new model was clearly required. With Metcalfe's imminent departure for Iraq – where he would model the portrait of King Ghazi I for its coinage – one was hurriedly produced by mid-December. Johnson expressed sincere trust that the new design would finally be approved by Coates and the New Zealand committee: As they are now doubt aware, the preparation of this piece has given the artist a very great deal of trouble.

A further rejection

Metcalfe, design for crown, November–December 1934.

Metcalfe's revised model was evidently well received. In February 1935 Mackay reported to Johnson that cabled advice has been received from the Dominion today approving of the amended design and asking you to proceed with the work. The delay ... is regretted, but apparently the NZ Committee is now satisfied. In May an order was processed by H.W.L. Evans, Superintendent at the Mint, for 345 specimen sets of the six denominations of 1935 coins, 95 of which would go into leather cases, as well as for a further 600 loose coins.

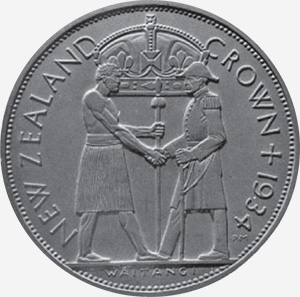

The order further stated that the whole work should be completed as soon as possible. It was not. On his visit to the Royal Mint in the same month, Sutherland was shown a trial N.Z. crown piece, which Johnson wanted me to O.K., but I stated that the power rested with Mr. Coates. The latter was on an emergency visit to London to safeguard Dominion meat export quotas. Johnson courteously but fatefully invited Coates to the Mint, suggesting you might perhaps like to come down here and strike the first piece. It was an exasperated Deputy Master who reported to Mackay several days later that Mr Coates and Miss Montague were not really satisfied with the legs and, in the circs [sic] shall do my best to persuade Metcalfe to make the necessary alterations. The Mint album bears the telltale documentation: 4th Design as finally adopted Not approved June 1935. One of the two known specimens of the rejected pattern coin is in the collection of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, Wellington and is on permanent display there.

Metcalfe produced a fifth and final model the following month. It contained several significant modifications that probably stemmed from Coates's most recent criticisms. The date was changed to the current year, a move that later inadvertently annoyed the New Zealand government in view of the fact that 1934 had been the annus mirabilis in Waitangi's recent history. The implication of the exergue inscription together with the date was that 1935 was somehow more significant. In addition, Nene's piupiu was raised to above knee-length and was given horizontal banding. The crown motif was increased to a size somewhere between the early, large version engulfing the heads of the two figures and the recent version just clear of them and made at Coates's insistence. As a consequence, an uncomfortable formal collision occurs between Nene's staff (taiaha) and the crown. In August Metcalfe visited the Mint to inspect the reduction punch, which he approved (though he still dislikes the design). His reaction was understandable, as the end result surely testifies more to Coates's fussiness and micromanagement than to any palpable aesthetic improvements.

Acceptance and apathy

By mid-October, three fresh specimen crowns were presented to the New Zealand High Commission for approval before the 945 then required were struck. In his response, Mackay indicated that authority was given to proceed with the order without waiting for the specimens to reach New Zealand. Ten more loose crowns were ordered and Mackay sympathetically told Johnson: You will doubtless not be sorry when the last case of Crown pieces finally leaves the Royal Mint. In the event, authorising the issue proved to be one of Coates's final acts as Minister of Finance. In late November his United-Reform coalition government was crushingly defeated by the Labour opposition in the general election. There is no evidence of interest in the coin from Coates's successor as Minister of Finance, Walter Nash, although orders were made for a further 173 pieces during the course of 1936. Another mini-controversy erupted in February of that year, when H.G. Williams, proprietor of the New Zealand Coin Exchange, Dunedin, vociferously complained to the Secretary of the Treasury about the inadequate packaging of the crown pieces:

I was astounded to find the Crowns were made up in Parcels of 20 pieces without even a piece of paper in-between each Coin to keep them from rubbing together ... These coins were made especially for collectors use and were proofed for that purpose and an extra charge of 50% was made. I have gone carefully through the 200 I have and cannot find one piece an advanced collector would with pleasure put into his cabinet.

The complaint was answered at the Mint by William Perry, who explained that these were among the 610 that had been ordered as ordinary coins and not as ... specimen pieces. If they had been ordered as specimens they would have been struck with polished dies, individually examined for defects, and each packed separately into a cardboard box. Perry recognised that loose coins, especially large crowns, were potentially vulnerable to scratching. Evidently Williams, the archetypal Kiwi huckster, was engaged in making up sets of uncirculated coins obtained from the bank and then selling them in boxes as specimen sets at eighteen shillings apiece. As such activity constituted competition with the genuine specimen sets issued officially it seemed fortunate that he has encountered difficulties in his activities.

Why were so few Waitangi crowns issued? In retrospect, it seems puzzling that all parties concerned – whether Johnson and Mackay in London, or Coates and Sutherland in Wellington – should have expended so much energy on such a limited release. One thousand, one hundred and twenty-eight coins represent a massive reduction from the ten thousand that Sutherland had initially envisaged. They certainly failed to earn the Treasury the profit that he had so confidently predicted. Due to the very small number of crown pieces ordered the cost per piece was necessarily high; artist's fees and work on the die cost over three shillings per coin. One immediate question that was never satisfactorily resolved was whether the crown was intended as a commemoration of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, as Coates had originally suggested in April 1934, or whether it would serve as the largest, highest value and most prestigious value coin of a complete set of distinctive New Zealand silver denominations.

In an article published in the New Zealand Numismatic Journal, Michael Humble claimed that it was not surprising that so few coins were struck:

Not only were there few coin collectors in New Zealand (the membership of the Numismatic Society was 110 at this time), but the country was in the middle of the Depression and few people had spare money to buy souvenir coin sets.

The price of loose crowns at 7s. 6d. apiece represented a fifty per cent premium on face value, while the 365 proof sets of 1935 silver coins cost a relatively steep 18s. 6d. mounted on cardboard and 25s. encased in leather. Yet the argument of unaffordability is not entirely convincing. By late 1935, New Zealand had emerged from the worst of the Depression. Although the incoming Labour Government has traditionally taken credit for this achievement, revisionist history has stressed Coates's underrated role in preparing the ground for economic recovery.

Instead, I would argue that aesthetic responses to the coin – or rather the lack of them – were a major explanatory factor. Sutherland's belief that the potential visual attractiveness of such a coin would stimulate demand was surely right; but this could apply in reverse were the actual product disappointing. Furthermore, with the death of George V on 20 January 1936, which coincided almost exactly with its arrival in New Zealand, the coin – at least on its obverse side – had become instantly obsolescent. Press interest in it was in any case minimal.

A single illustration of the crown, with a brief descriptive caption, appeared in Wellington's morning newspaper, the Dominion in January 1936, but there is little or no further recorded coverage elsewhere. Perhaps this illustrates apathy rather than antipathy. Anecdotal evidence from the (later Royal) Numismatic Society of New Zealand's oldest surviving member, George Barr (b. 1916), recalls his friend John Lawson, a Bank of New Zealander teller, being instructed to sell five crown pieces. Saving one for himself, Lawson targeted public houses in the Wairarapa, where the response was lukewarm. The paucity of requests from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand for specimen crown pieces during the late 1930s and early 1940s lends further support to this argument. By contrast, the 1940 commemorative half-crown, which had a minting of 100,800, rapidly disappeared from circulation into coin collections.

Its availability at face value doubtless contributed to this. Significantly, its design by Berry's friendly rival Leonard Cornwall Mitchell – with adaptations by Metcalfe – while somewhat finicky, is far prettier than that of its bigger, elder and scarcer sibling. The relative aesthetic mediocrity of the crown probably did little to make it coveted for a number of years yet. The value of this beautiful specimen of the Numismatic Art, as E.J. Arlow described it in the New Zealand Numismatic Journal, stood at a fairly modest £30 in 1960. Comparing it with equivalent Canadian and American silver coins, Arlow implied that the crown's rarity should make it command a far higher price. History has subsequently vindicated him; by 1984, the coin enjoyed a catalogue value of $NZ 4,000 (£1,700) and one graded as extremely fine fetched $NZ 8,750 just before the time of writing.

L.C. Mitchell and Percy Metcalfe, 1940 half-crown.

A numismatic embarrassment?

In the short term, response to the crown and its design appears to have been one of ill-concealed embarrassment, which was felt by all major players. Metcalfe, as stated above, disliked it. References to the coin in the recorded minutes of the New Zealand Numismatic Society were few. Pointedly, a few weeks after its arrival, The design of the Crown piece was not discussed at the March 1936 meeting. In October, the architect and numismatist Percy Watts Rule contrasted what he called the excellent lower denominations with the only disappointment in the N.Z. set ... the Crown piece (the only one not by Kruger Gray). The flat wooden figures might be historic, but they were not artistic. Sutherland echoed these comments in a letter to Johnson: The final result is pleasing and historic, but I cannot help thinking that Mr. Metcalfe was not happy with the composite design. It is certainly not his best work, but admittedly he had to please others – Sutherland included.

In response, while he defended Metcalfe as a very skilful artist and full of invention, Johnson admitted that The design of the New Zealand Crown was, as you surmise, not really sympathetic to him; indeed, most of us thought the standing figures unsuitable for a coin, and I doubt whether any other artist would have ultimately made a better job of it. Five years later, in his Numismatic History of New Zealand, Sutherland reiterated how It was unfortunate that Mr. Kruger Gray was not commissioned to complete the series, in order to retain unity of treatment.

Yet some good perhaps did emerge out of the 1935 Waitangi crown. Its long delay acted as an incentive for the future halfpenny, penny and commemorative half-crown to be planned sufficiently far ahead to enable the best designers to compete, and to enable the coin to be issued in good time for the Centennial celebrations. Sutherland used the coin as a basis for an article in the New Zealand School Journal, in which he explained the significance of the joining together, under the crown, of the Maori and British races, using a vocabulary eminently characteristic of the period. As a passionate advocate of decimalisation, Sutherland furthermore suggested that it would be a comparatively easy matter to adapt our present silver coins for use in a crown-cent decimal system. That, however, is another story.

References

- Arlow, E.J., [E.J.A.], 1960. N.Z. Waitangi Crown 1935, New Zealand Numismatic Journal 10/1, 291–3.

- Ballara, A., 1990. Nene, Tamati Waka, The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography: Volume One 1769–1869 (Wellington), 306–8.

- Bassett, M., 1995. Coates of Kaipara (Auckland).

- Bindman, D. (ed.), 1979. John Flaxman, R.A. (London).

- Colenso, W., 1890. The Authentic and Genuine History of the Signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand, February 5 and 6, 1840 (Wellington).

- E.J.A. 1960. See Arlow 1960.

- Forrester, H., 2006. The Other Percy Metcalfe, The Medal 49, 22–35.

- Frayling, C., 2003. Egyptomania, in C. Benton, T. Benton and G. Wood (eds), Art Deco 1910–1939 (London), 40–9.

- G.T.S. 1968. See Stagg 1968.

- Hargreaves, R.P., 1972. From Beads to Banknotes: The Story of Money in New Zealand (Dunedin).

- Humble, M., 1992. The Waitangi Proof Set Revisited, New Zealand Numismatic Journal 70, 13–17.

- King, M., 2003. The Penguin History of New Zealand (Auckland).

- McKinnon, M., 2003. Treasury: The New Zealand Treasury 1840–2000 (Auckland).

- Moon, P., 1998. Hobson: Governor of New Zealand 1840–1842 (Auckland).

- Renwick, W., 2004. Reclaiming Waitangi, in W. Renwick (ed.), Creating a National Spirit: Celebrating New Zealand's Centennial (Wellington).

- Royal Numismatic Society of New Zealand, 2005. The New Zealand Numismatic Society Transactions 3 Vols: 1. 1931–1936; 2. 1936–1941; 3. 1941–1947.

- Seaby, P., 1985. The Story of British Coinage (London).

- Stagg, G.T. [G.T.S.], 1968. Alan Sutherland, F.R.N.S., F.R.N.S.N.Z., F.N.S.S.A. New Zealand Numismatist Extraordinary, New Zealand Numismatic Journal 12/3, 125–7.

- Stocker, M., 2000. Coins of the People: The 1967 New Zealand Decimal Coin Reverses, BNJ 70, 123–38.

- Stocker, M., 2001. Queen Victoria Memorials in New Zealand: A Centenary Appraisal, Bulletin of New Zealand Art History 22, 7–28.

- Stocker, M., 2005. A Very Satisfactory Series: The 1933 New Zealand Coinage Designs, BNJ 75, 142–60.

- Sutherland, A., 1941. Numismatic History of New Zealand (Wellington).

- Tye, J.R., 1984. The Image Maker: The Art of James Berry (Auckland).

- Wallace, P., 2007. He Whatu Ariki, he Kura he Waero: Chiefly Threads, Red and White, in B. Labrum, F. McKergow and S. Gibson (eds), Looking Flash: Clothing in Aotearoa New Zealand (Auckland).

Acknowledgements. This article was originally presented as a paper at the third conference of the Numismatic Association of Australia, Macquarie University, on 29 November 2009. I am most grateful to Philip Attwood, Ann Compton, Rosi Crane, Dr Edward Hanfling, Colin Pitchfork, Martin Purdy, Iain Sharp, Dr Allan Sutherland, Dr Patricia Wallace and Dr Philip WardJackson for their assistance with the article. 1